Lecture Series

Valley of Virginia, 1820s

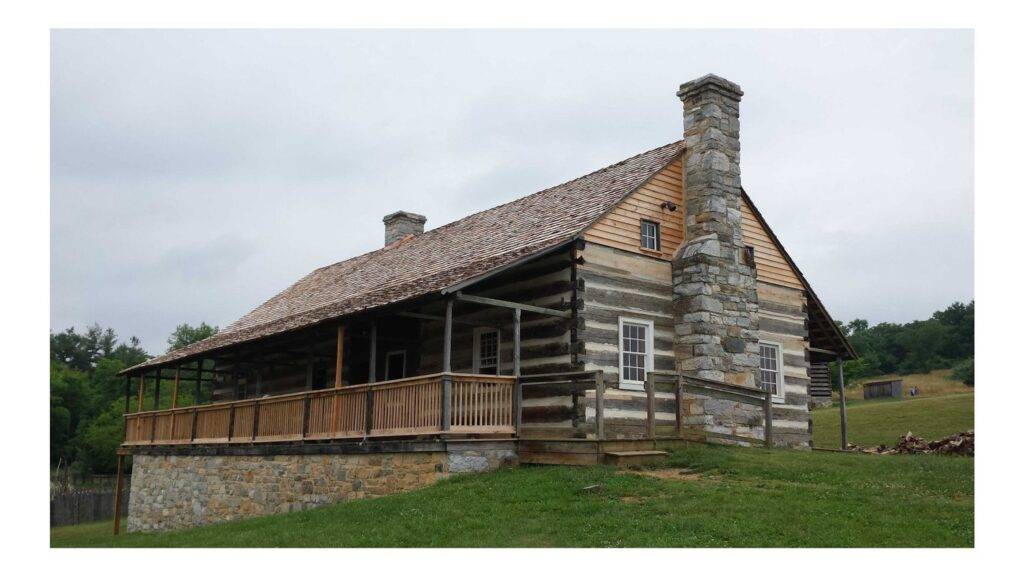

The 1820s American Farm was originally built by a German immigrant farmer in 1773 in Rockingham County, Virginia. Anglo-American influences entered the Virginia German lives slowly. By the 1820s, English furniture forms, such as the chest of drawers, began to appear in their houses. They became tea and coffee drinkers and began using imported English dinner plates and teacups. This exhibit shows how the various cultures merge over the 50 years which span the periods of the American Revolution and the Early Republic.

By the 1820s, the different peoples who settled the Valley of Virginia had lived together for several generations. They were shaped by the common experiences of settling on the frontier, the American Revolution, the founding of the United States, and the market revolution. As a result of these shared experiences, ethnic differences began to fade.

Cultural persistence remained strongest among the Virginia Germans. Many Virginia Germans maintained their language and unique customs throughout the 1800s, but after 1820 they also began to move toward mainstream American culture. Ethnic distinctions among German, Scots-Irish, and English settlers remained, but intermarriage, culturally diverse rural neighborhoods, and the emergence of a market economy made these distinctions less pronounced.

The main distinction within the Valley’s population was between white and Black, free and enslaved. The vast majority of African Americans (about 25% of the population in 1820) were enslaved, and those that were free did not enjoy equal rights or opportunities. African Americans created families and communities whenever they could, but they were often torn apart due to the expansion of the country.

By the 1820s, Virginia enslavers were selling large numbers of enslaved African Americans to the new states of Louisiana, Mississippi, and Alabama where cotton and sugar were becoming major commodities. Although there had long been a domestic slave trade in the United States, the end of transatlantic slave trade from Africa in 1808 greatly expanded its scope and distance, and Virginia emerged as a leading exporter of enslaved people.

The exact number of enslaved men, women, and children who were forcibly removed from Virginia during these years is unknown, but between 1810 and 1860, an estimated one million slaves were taken from their homes in the Upper South to the Lower South. Valley enslavers participated in the domestic slave trade, and one of the overland routes to the new states used by slave traders passed through this area.

Only a small part of the Valley’s white population enslaved people, and most of those only held a few in bondage. However, many of the settlers who did not keep people in bondage themselves, still participated in the institution of slavery and profited from the enslavement of African Americans. For example, it was a common practice for white settlers to rent unfree laborers, sometimes for a year or more. Many enslaved and free African Americans worked in households as domestic servants, on farms as laborers, and in the small industries that operated in Valley, often practicing crafts such as milling or blacksmithing.

Much farm labor was provided by enslaved African American, but landless white, free Black day laborers, and the farming family also participated in the numerous tasks which agricultural production entailed. Having sufficient labor was vital on Valley farms, particularly during the plowing, sowing, and harvest seasons, because there was little mechanization of agriculture before the mid-1800s. Seed was still sown by hand, and reaping hooks and grain cradles were used to harvest grain. Plows were pulled by horses, but most farmers still used wooden moldboard plows sheathed in sheet iron, and breaking the soil with this implement was a hard, difficult task.

Farmers in the Valley of Virginia were engaged in mixed farming dominated by grains and livestock. The main cash crop was wheat, which was ground into flour at local mills for export to eastern markets. Other crops included corn, rye, barley, and oats, which were used as animal feed or distilled into liquor. Livestock included horses, which were used as draft animals, cattle, swine, and sheep. Cattle and swine were particularly important. Cattle were driven to eastern cities for sale, while hogs were raised primarily for home consumption.

Migration streams through Kentucky and Ohio continued on to the “Old Northwest,” the territory that later became the states of Indiana and Illinois. Virginians were prominent among the migrants who settled in the southern reaches of this territory.

The Louisiana Purchase in 1803 more than doubled the size of the young nation. American settlers, many of whom were Virginians, quickly moved into the future states of Missouri, Louisiana, and Arkansas.